Against what may or may not be good logic, I’ve begun a new sour beer project. My goal is to successfully create a delicious sour beer fermented only from airborne yeast and bacteria. There is something beautiful about the idea of successfully producing a delicious sour beer that reflects the micro-flora present where I live. I love the tangible connection that can be made with world-renowned Lambic brewers who continue to brew traditional spontaneously fermented beers (as well as American craft brewers like Allagash, Jester King, and Russian River). I am keeping this project as wild as possible; I will not be culturing yeast from fruit, grains, bottle dregs, or any other source, rather only what I can capture across the cool evening breeze.

The Internet is full of stories both of success and failure when it comes to truly spontaneous beer. Whenever I attempt a technique that includes a high probability for failure, I try to set as many variables in my favor as possible to get a successful end result. There are no guarantees for success in a project like this, but taking a few simple measures can greatly increase your odds. Using this logic, I decided that running multiple samples and testing their qualities before pitching into a full 2.75 gallon batch of beer was the way to go. This was especially important given the fact that I live an dense urban environment with little vegetation and no fruit bearing trees that could be attractive homes for wild yeast.

My Process

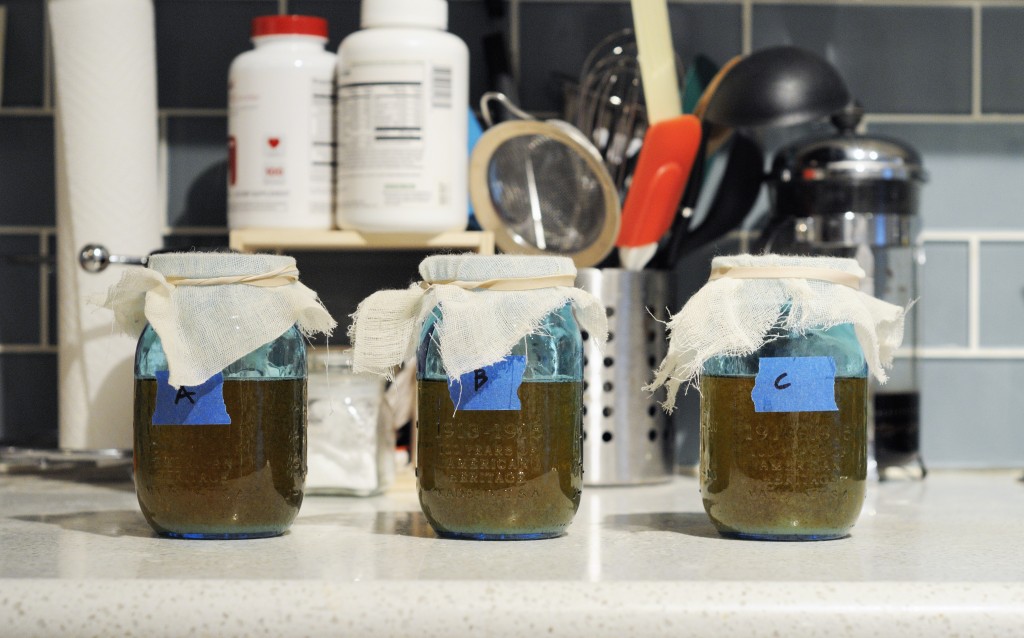

Initially I prepared (3) 8 oz. samples of sanitary 1.030 OG wort and placed them boiling hot into pint sized mason jars. I added 0.3 ml of 88% lactic acid to each sample in order to acidify each below pH 4.5. My goal is to inhibit pathogens from growing in the wort as well as non-pathogenic bacteria that can produce objectionable flavors. Since I would be tasting the wort, I wanted to minimize terrible tasting samples as well as ones that could potentially make me sick.

Initially I prepared (3) 8 oz. samples of sanitary 1.030 OG wort and placed them boiling hot into pint sized mason jars. I added 0.3 ml of 88% lactic acid to each sample in order to acidify each below pH 4.5. My goal is to inhibit pathogens from growing in the wort as well as non-pathogenic bacteria that can produce objectionable flavors. Since I would be tasting the wort, I wanted to minimize terrible tasting samples as well as ones that could potentially make me sick.

Each of the three samples were placed around my apartment. One was located on the roof of my building, one in front of an open window at the rear of my apartment, and one in front of an open window at the front of my apartment. Each were covered with a couple layers of cheese cloth to prevent any insects from entering the sample and then left to cool for approximately 24-hours. After 24-hours I fitted each jar with a lid and airlock to create an anaerobic environment, providing control of another variable and putting selective pressure on the organisms growing in the wort.

I completed this experiment in the late fall, which according to American Sour Beers offers the best probability for culturing yeast and bacteria that will have a positive fermentation character.

After approximately one-month, I completed a sensory analysis of each sample (smell and taste). In hindsight, I should have also taken pH and gravity measurements.

Sample A – In Front of Window – Small filmy pellicle. Cabbage, some baby diaper. No apparent alcohol flavor.

Sample A – In Front of Window – Small filmy pellicle. Cabbage, some baby diaper. No apparent alcohol flavor.

Sample B – Outside on Roof – Small filmy pellicle. A couple spots of white fluffy mold. Some alcohol on nose. Light rubbery phenol.

Sample C – In Front of Window – Small filmy pellicle. Cabbage. Some oniony aromas. Pretty sweet, low alcohol.

Encouraged by the initial results, I stepped each into a three new 300-ml sanitary starters. Each were allowed to ferment for another month under airlock.

Sample A – Very sweet. Didn’t appear to ferment much. Clean.

Sample B – Quite sour. Some definite plastic-like phenolics and slight alcohol. Some pleasing barnyard notes.

Sample C – Reminiscent of pickle juice. The most sour. Definite alcohol on nose. Not very pleasant.

After the second round of fermentation, I decided that Sample B (the sample pulled from my roof) was the most pleasing (or least offensive). I pitched it into a fresh 1200 ml starter (also under airlock) and made preparation to brew a full 2.75 gallon batch. For my recipe, I decided on a simple golden grain bill to act as a clean slate for the culture to express itself.

2014 Brambic Recipe

Size: 3.25 gal

Size: 3.25 gal

Efficiency: 75%

Attenuation: 90% (estimated)

Original Gravity: 1.049 SG

Terminal Gravity: 1.005 SG (estimated)

Color: 3.33 SRM

Alcohol: 5.71% ABV (estimated)

Bitterness: 0.0 IBU

Grist:

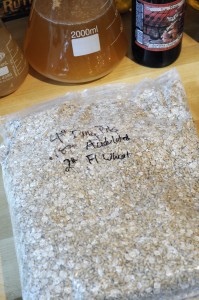

4.0 lb (64.6%) Dingemans Belgian Pils

2 lb (32.3%) Briess Flaked Wheat

3 oz (3.0%) Weyermann Acidulated Malt

Mash Regiment:

A turbid mash regiment (basically a thin decoction) was completed through the steps below. A Ferulic acid rest was completed to encourage the formation of 4-vinyl guaicol which Brettanomyces can theoretically convert into 4 ethyl-guiacol which produces some of the ‘funky’ aromas and flavors that Brettanomyces is known for. A short Beta rest was followed by a very high Alpha rest to encourage a dextrinous wort and protracted secondary Brettanomyces fermentation.

113 °F – Ferulic Acid Rest – 10min

136 °F – Protein Rest – 5min

150 °F – Beta Rest – 20min

162 °F – Alpha Rest – 30min

168 °F – Mashout Rest – 5min

Water Treatment:

Extremely Soft NYC Water

4g Gypsum (to mash)

4g Calcium Chloride (to mash)

Hopping:

1.25 oz AGED Cascade (0% AA) – 90 m

Kettle Additions:

0.5 ea Whirlfloc Tablets (Irish moss) – 15 m

0.5 tsp Wyeast Nutrient – 10 m

Yeast:

1200ml Brambic Spontaneous Culture

Fermented at ambient temperatures (70°F or so)

The beer will be allowed to ferment for at least a year until packaging.