Seven months have passed since I moved cross country to Brooklyn. Life has a way of getting in the way of hobbies and my new brewery build was shifted to the back burner. Luckily, things are looking up. New equipment has been ordered and my first Brooklyn batch is only a couple weeks out.

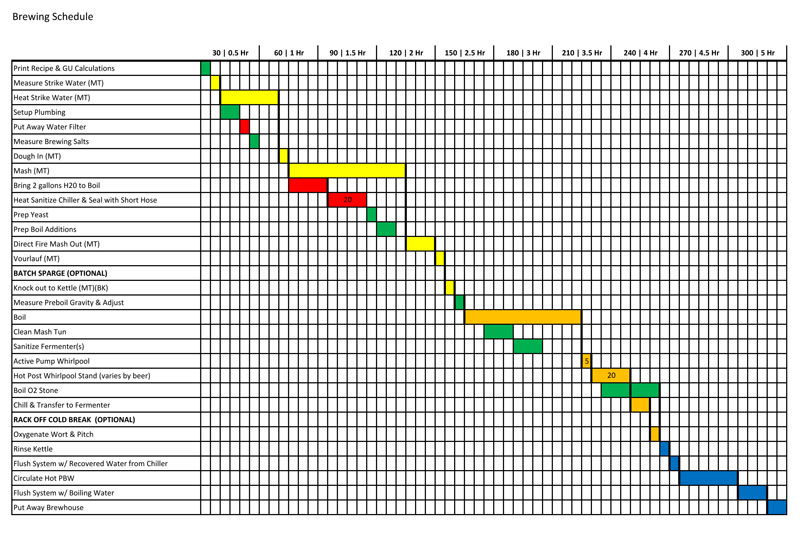

Home brewery design has been on my mind a lot. Sizing components, designing wort transfer processes, handling the logistics of boiling on a puny stove and thinking about the items I’d change from my original brewery have been integral to my new brewery’s design. Among things that I wanted to implement in the new design:

- Pump transfers of liquid. No more lifting heavy (and hot) vessels.

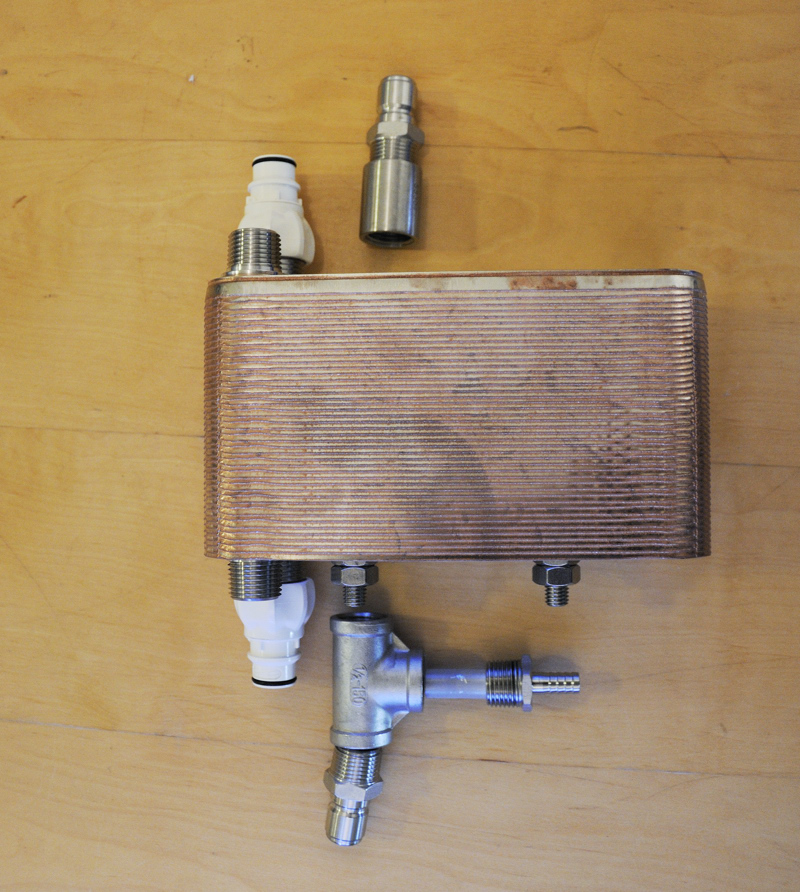

- Use a plate chiller to increase cooling efficiency. Plumb vessels and pump to allow circulation back into kettle post-chill in order to utilize a whirlpool and minimize cold break from getting into the fermenter. It doesn’t appear many people are doing this, and I may abandon the process it if it proves to have little benefit.

- Create a tangential inlet into the kettle to allow for effective whirlpools.

- Use stainless steel quick disconnects throughout — because they’re cool.

- Plan for easy future integration of a RIMS tube w/ PID controller.

- Plan for easy future integration of a hop back.

- Build the brewery around the smaller volumes that fit the type of brewer I am.

- Use an electric heat element to jump start boils. Don’t electrocute myself.

Paramount to my brewery’s design is the volume of the various vessels. It is important to appropriately size my new brewery for the typical volumes and specific gravities I intend to use it for. By analyzing my own personal brewing interests, I’ve come up with the following typical brew lengths which can be used to size my equipment.

Typical Brew Lengths

- The Daily Drinker – 3 gallons (post boil) up to 1.080 original gravity.

Easily packaged in a 3 gallon corny keg and served on draft. Typical brew length.

- Experimental Split Batches – 2.5 gallons (post boil) up to 1.120 original gravity.

The perfect volume for experimentation. Easily split into secondary 1 gallon glass vessels for different treatments. Capable of producing very high gravity wort.

- Recipe Development Batches – 1.5 gallons (post boil) up to 1.120 original gravity.

I get most of my enjoyment from the brewing process and learning about the implications recipe and process design have on the final batch. This batch size and gravity allows for frequent brewdays and flexibility.

Vessel Sizing

The vessels I’ve put into my brewery are designed around the gravity and volume of the typical brew lengths. Of the above scenarios, the ‘Experimental Split Batches’ has the highest gravity demands and thus dictates the mash tun sizing. The calculations showing the mash tun size requirements are below.

Constants Used for Calculations

70% efficiency (batch sparge)

60% efficiency (no sparge)

Mash Thickness: 1.25 qt. / pound water (batch sparge)

Mash Thickness: 2.25 qt. / pound water (no sparge)

35 Gravity Units per Pound of Malt

1 lb grain = 0.32 quarts (volume)

0.15 gallon / pound (grain water absorption)

Sizing Calculations

Experimental Split Batches:

2.5 Gallons @ 1.120 Original Gravity

2.5 x 120 = 300 Gravity Units

Mash Volume Calculation (Batch Sparge):

300 GUs / 35 PPG / 0.7 (efficiency) = 12.24 lbs grain = 3.92 qt. = 0.98 gallons

3.825 gallons Strike Water @ 1.25 qt/lb

Total mash volume: 4.8 gallons

Mash Volume Calculation (No Sparge):

300 GUs / 35 PPG / 0.6 (efficiency) = 14.28 lbs grain = 4.57 qt. = 1.14 gallons

8.03 gallons Strike Water @ 2.25 qt/lb

Total mash volume: 9.17 gallons

Kettle volume = 8.03 (strike volume) – 2.14 (grain absorption) – 0.5 (dead space) = 5.39 gallons

Mash Tun Size

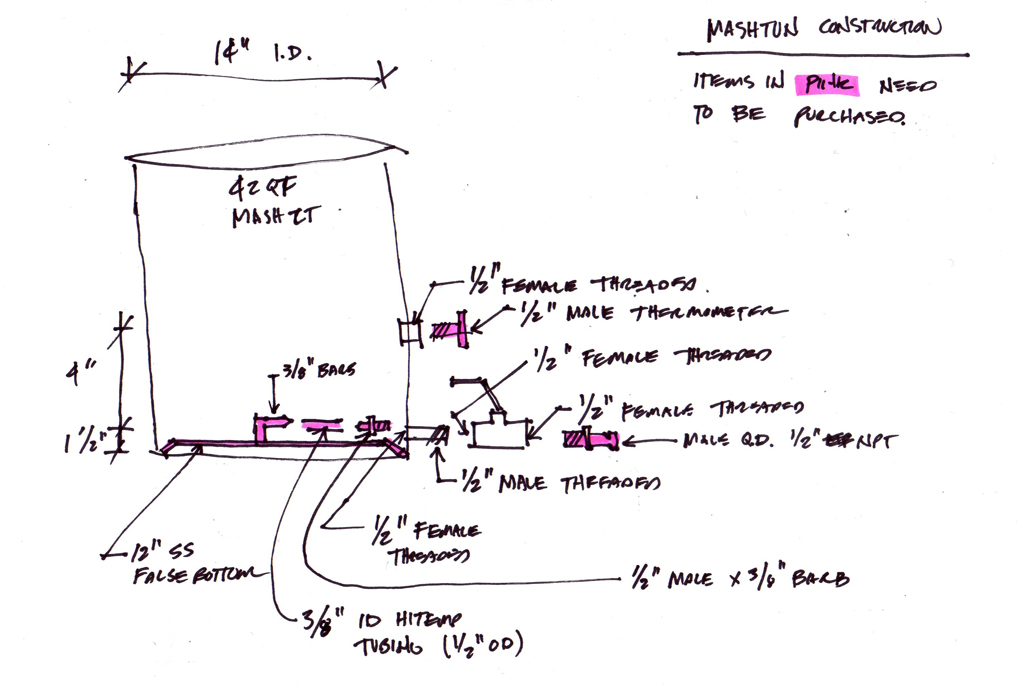

Of the brew length typologies above, the ‘Experimental Split Batch’ (batch sparge) requires the largest volume mash tun (9.17 gallons). At the last NHC I won a 42 quart Polar Ware stainless steel kettle which should work well as a mash tun once it is insulated. It is stainless steel which will allows me to heat my strike water directly in the mashtun, and possibly do some direct fired mashes with the aid of a pump and stirring action. This is a large mash tun and will likely be problematic for extremely small batches. My plan is to design my hot liquor tank with valves, a false bottom, and insulation so that it may be used as an alternative mash tun for small batches.

Hot Liquor Tank Size

Strike water will be directly heated in the mashtun. When batch sparging, a separate 3-gallon vessel will be used to heat sparge water.

Kettle Size

My maximum batch size is 3 gallons. If these batches start with 3.5-4 gallons of volume pre-boil, I should be able to use a 5-gallon boil kettle. For batches requiring very high gravities, I will likely run off more wort than can fit in this kettle and boil for long periods. In this case, I will likely split the boil into multiple vessels.

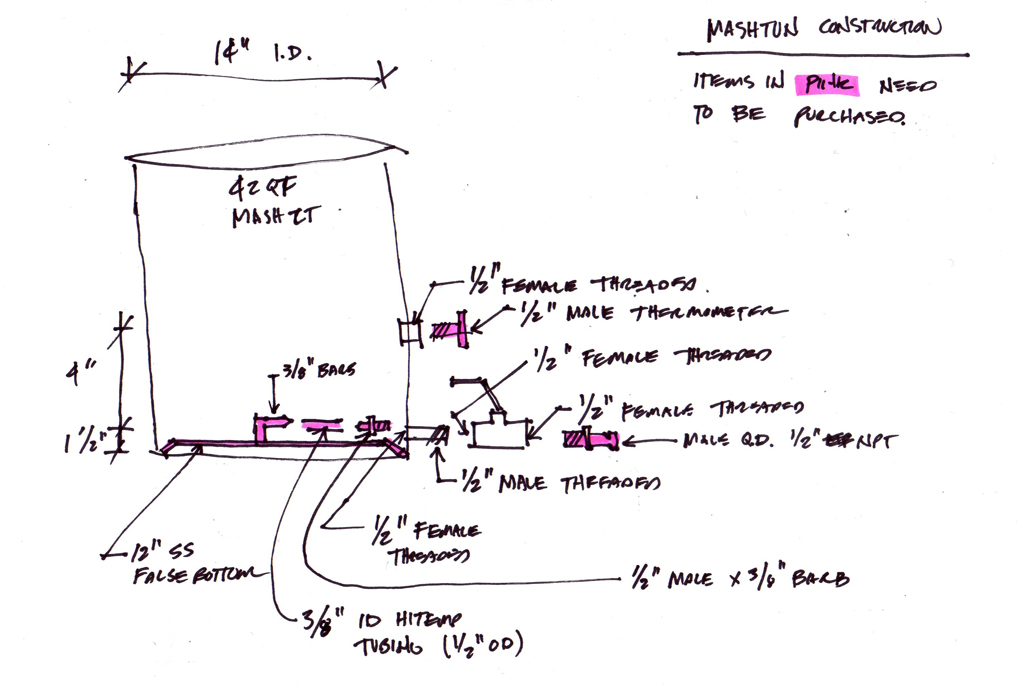

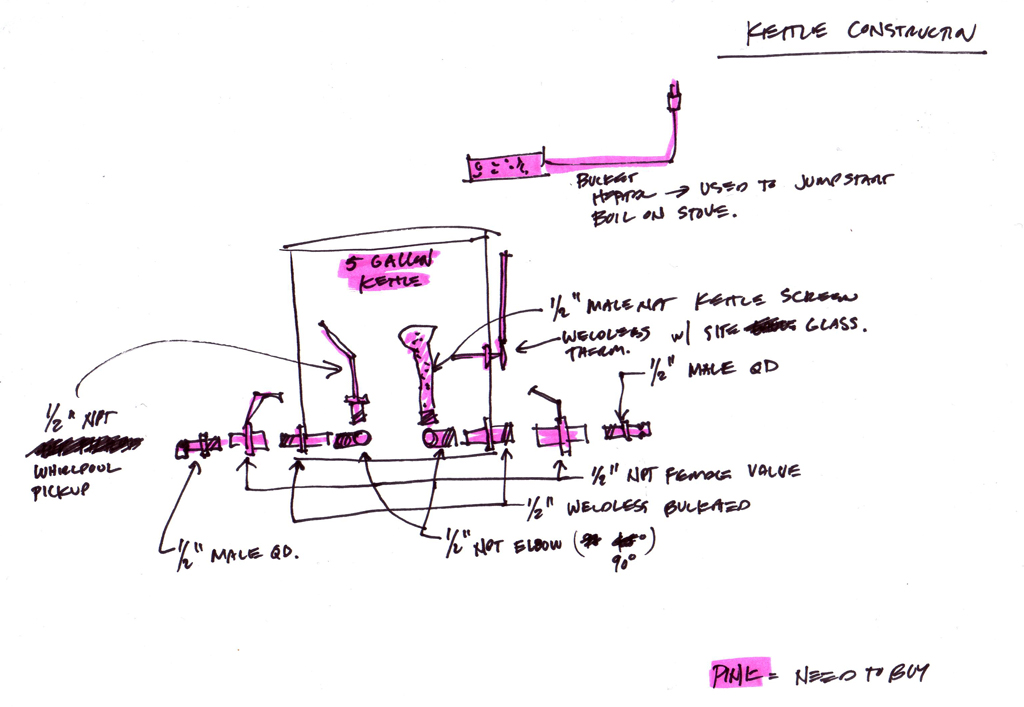

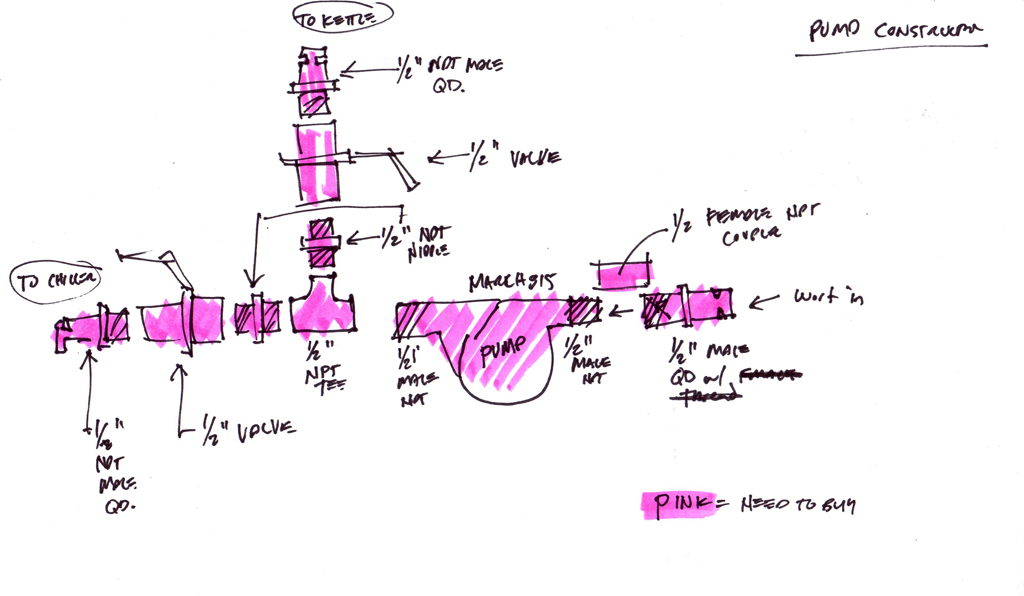

For my next post, I’ll photograph the brewery’s test run and breakdown the parts and processes designed into the brewery. In the meantime, check out the sketches of the brewery’s main components used to determine how everything connects and works together.

Mash: 42 quart stainless steel mash tun. Features SS false bottom, ported thermometer, and stainless steel quick disconnects.

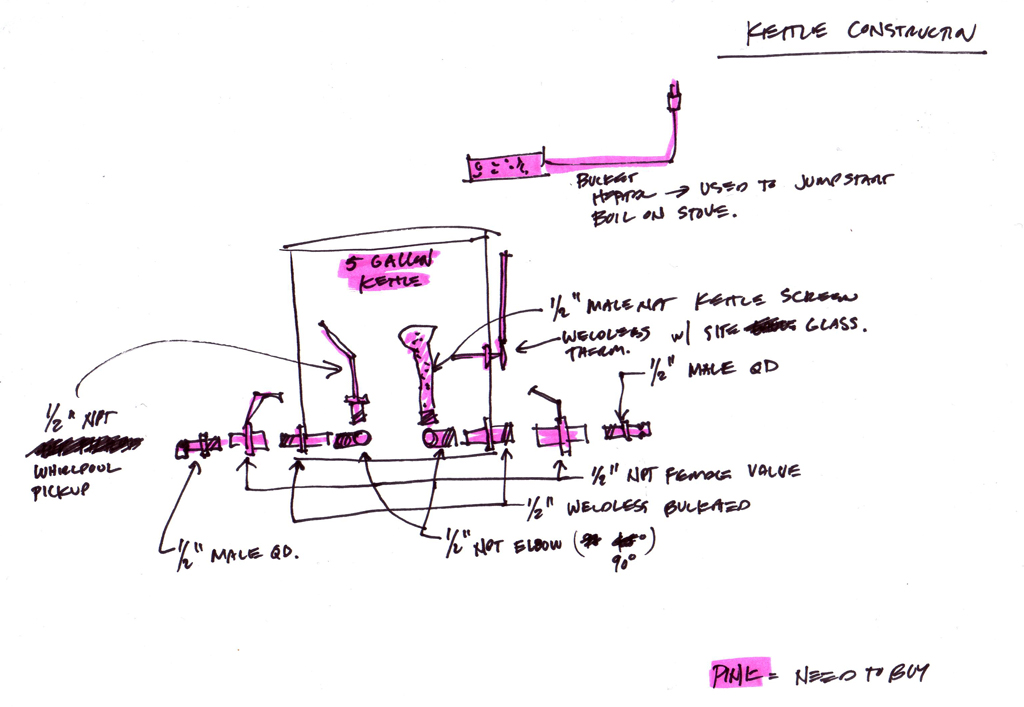

Boil: 5-Gallon stainless steel kettle. Features two liquid ports (one ‘out’ and one ‘in’ for whirlpool functionality), a sight glass with thermometer, and supplemental heat source via a bucket heater.

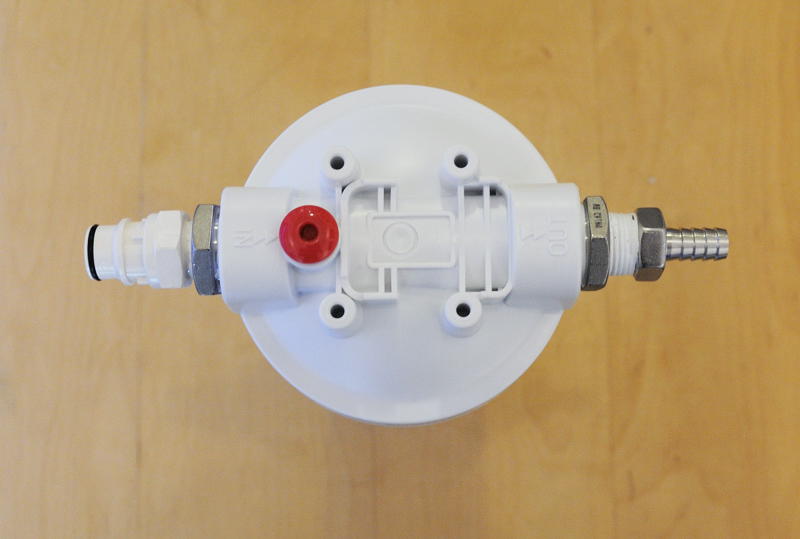

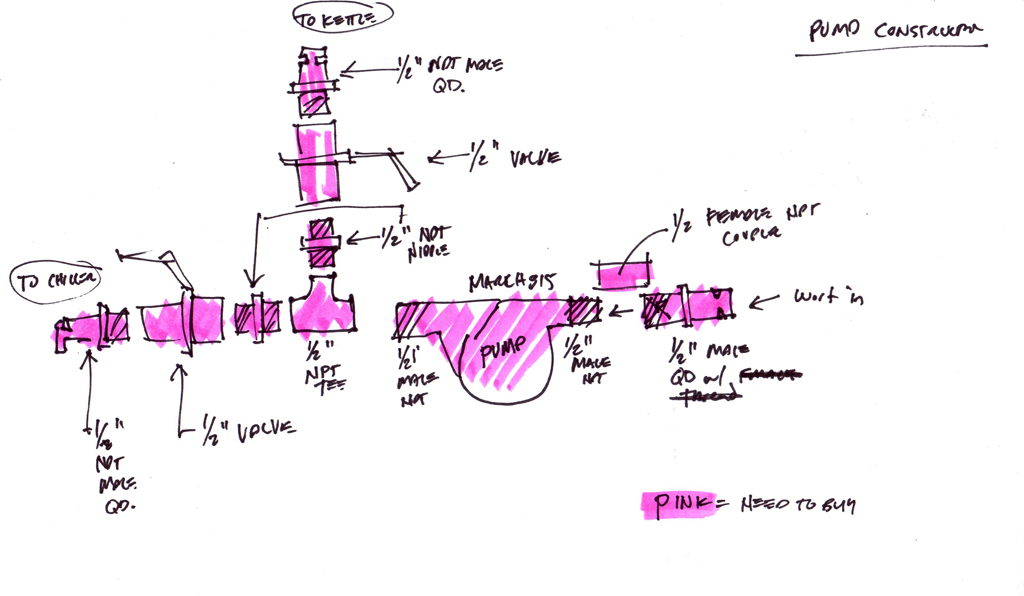

Wort Transfer: March pump with stainless steel quick disconnects. There is a tee with valves allowing for recirculation directly into kettle or through the plate chiller that is attached in series.

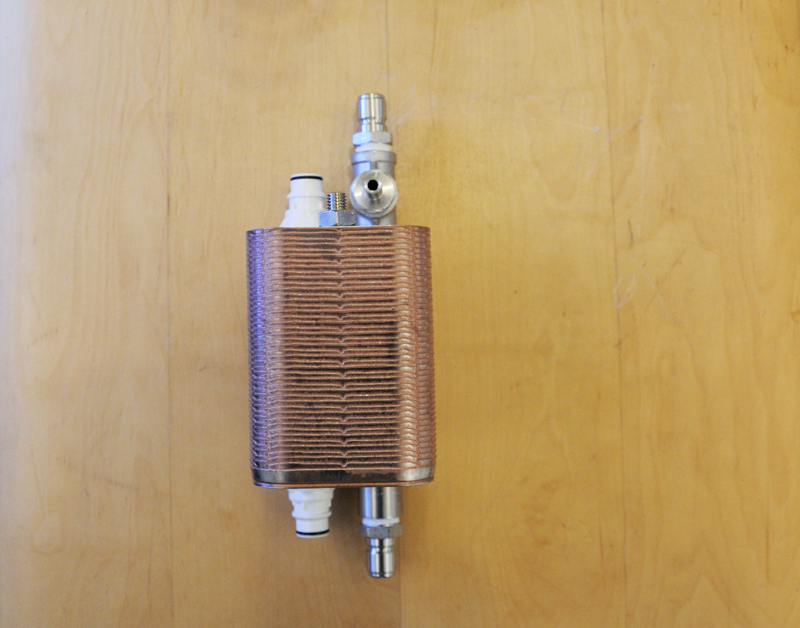

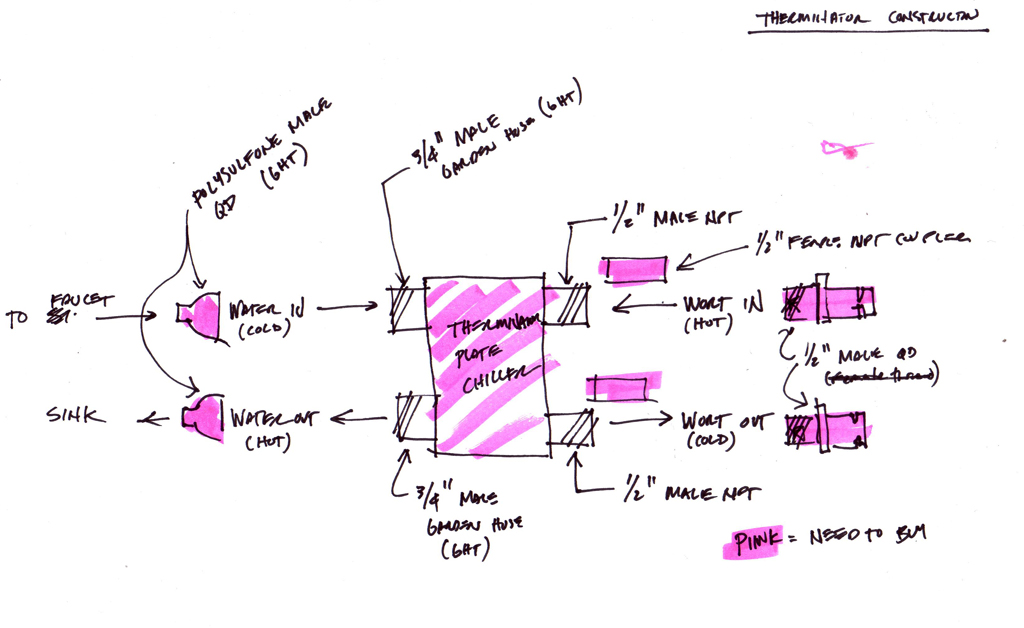

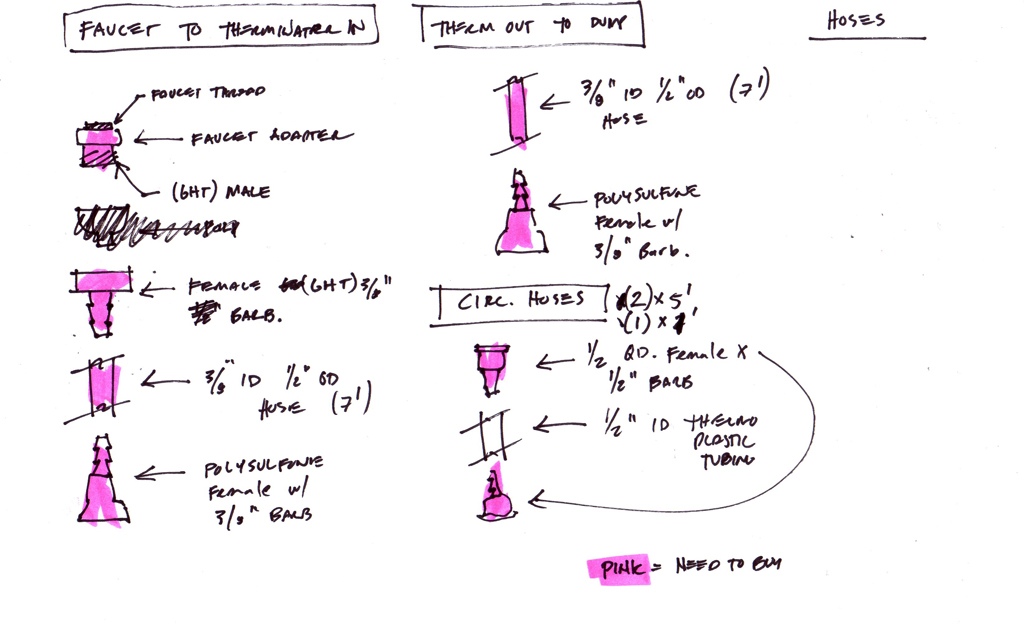

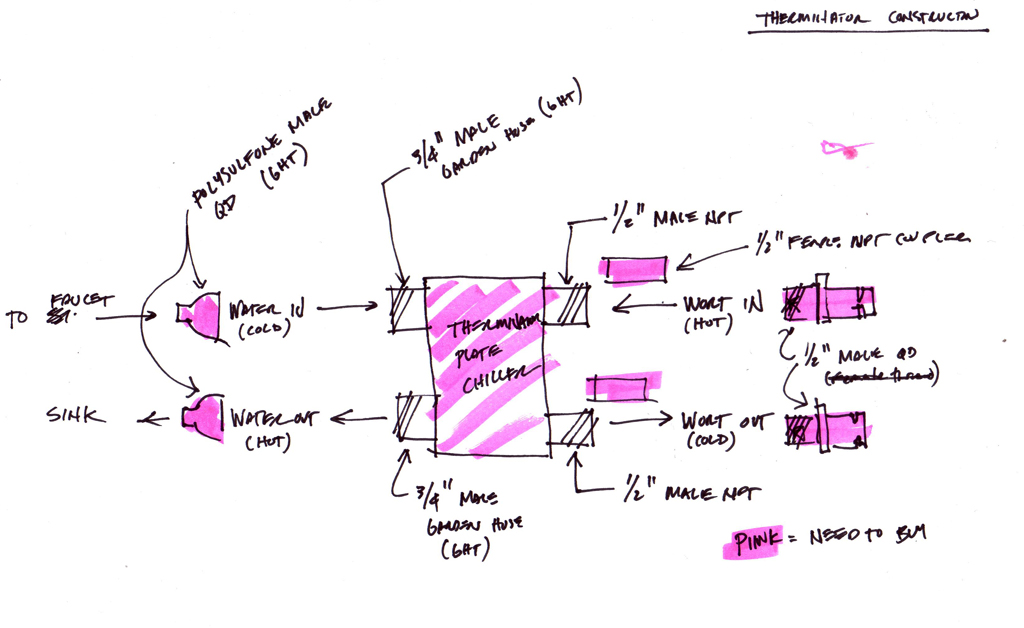

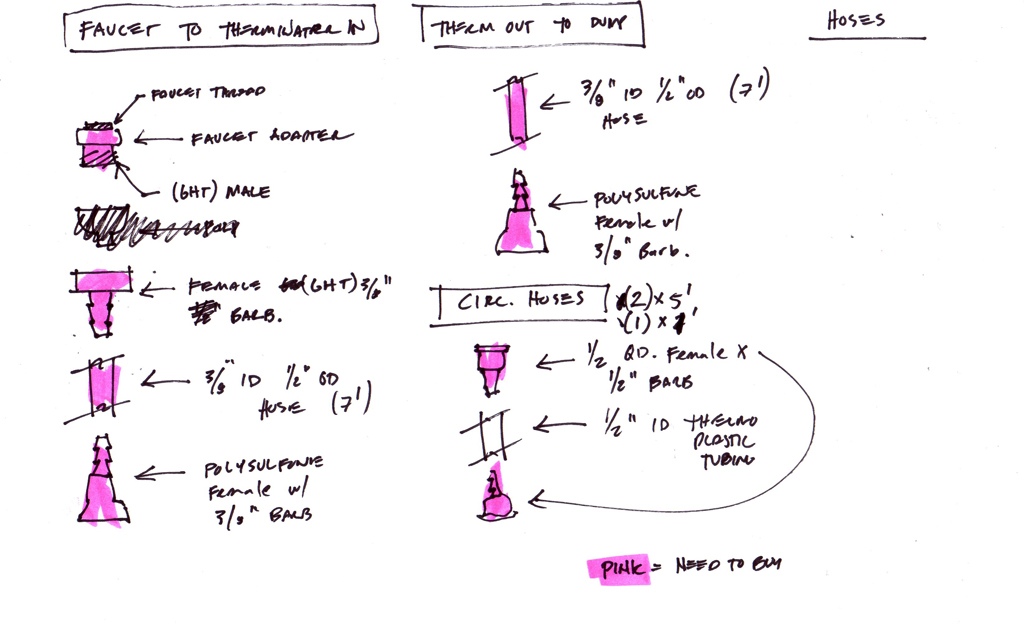

Chill: Plate chiller with appropriate stainless steel quick disconnect fittings. Polysulfone quick discounts connect the chiller to my cold water source (my kitchen faucet).

All hoses are designed with appropriate food safe thermo-plastics and stainless steel quick disconnects where possible.