Using blankets and coats to insulate my mashtun.

I love sour beer. I love simple beers. I love Berliner Weisse.

Berliners are low in alcohol and crisp, featuring a clean lactic sour character that can be quite tart and thirst quenching. They are easy drinking and sessionable. The best ones have an almost yogurt-like tartness produced by a lactic fermentation and complemented by a light and almost crackery wheat malt character.

The key to this Berliner recipe is creating a clean and substantial tart sourness using sour mash techniques. The beauty of a sour mash is that you don’t have to grow potential contaminants on the cold side of your brewhouse. The basic process involves mashing as you typically would and then post conversion inoculating the mash with a portion of raw grain (some inoculate with a commercial lacto pitch). The mash is allowed to naturally sour before boiling, chilling, and pitching yeast. Successfully sour mashing is all about setting the right environment for naturally occurring lactobacillus on the grain to thrive while discouraging other microbial action (molds, other bacteria, wild yeast, etc.). While researching sour mash, I ran into a lot of sources describing the putrid aromas that they can sometimes produce. Descriptors like gym socks, rotten vegetables, stinky cheese, and baby diaper are common when sour mashes are poorly executed, and are completely avoidable. By manipulating pH, temperature, and exposure to oxygen you can encourage clean lactobacillus growth while minimizing the growth of unwanted organisms.

pH – My recipe includes a large charge of acidulated malt, post sugar conversion, used to drop the mash pH into a range that lactobacillus can thrive at, but unwanted organisms do not.

Heat – My recipe inoculates the sour mash at the upper end of the temperature range that lactobacillus can thrive (126° F) and keeps the mash hot for 48 hours, using care to not allow the mash temp to drop below 106° F.

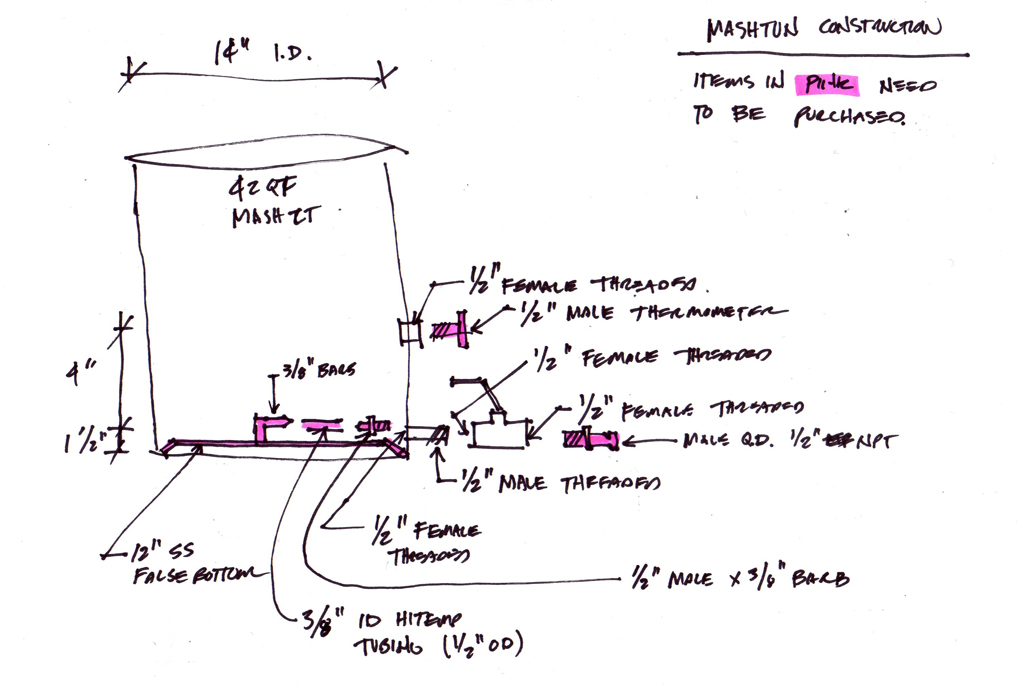

Oxygen – Lactobacillus thrives in anaerobic environments, while other organisms that throw off-flavors are aerobic. In order to encourage lacto fermentation, it is important to purge the mash tun using CO2 and seal it in order to prevent oxygen exposure. Additionally, I used de-aerated water (boiled) to mash with and was careful to not excessively stir the mash.

Recipe

Size: 3.24 gal

Efficiency: 76% (measured)

Attenuation: 72% (measured)

Boil Length: 30 minutes

Original Gravity: 1.036 (measured)

Terminal Gravity: 1.010 (measured)

Color: 3.03 SRM

Alcohol: 3.4% ABV (calculated)

Bitterness: 5.0 IBUs

Ingredients:

2.5 lb (52.6%) Bohemian Pilsner Malt

1.75 lb (36.8%) White Wheat

2 oz (2.6%) Acidulated Malt (for mash pH correction)

6 oz (7.9%) Acidulated Malt (added during 156° F rest to acidify sour mash post sugar conversion)

0.25 lb (0.0%) Rice Hulls (added during lauter)

8 g (100.0%) Hallertauer Hersbrucker (4.3%) – boiled 30 m

0.5 ea Whirlfloc Tablets (Irish moss) – boiled 15 m

0.5 tsp Wyeast Nutrient – boiled 10 m

1 ea WYeast 1007 German Ale™

Mash:

60 min – Rest at 148 °F

10 min – Rest at 156 °F

10 min – Mashout at 168 °F

Sour Mash:

1. De-aerate mash strike water by boiling.

2. Cool mash water to strike temperature.

3. Complete mash regiment and let it cool in mash tun to 126°F. Minimize stirring and aeration of wort.

4. Add 4 oz uncrushed pilsner malt to inoculate wort.

5. Cover mash bed with aluminum foil, purge with CO2, and seal mashtun.

6. Wrap mash tun in blankets and rest 48 hours.

7. Add boiling H2O to increase sour mash temp as required.

Brew Day:

1. Mash out grain bed.

2. Lauter

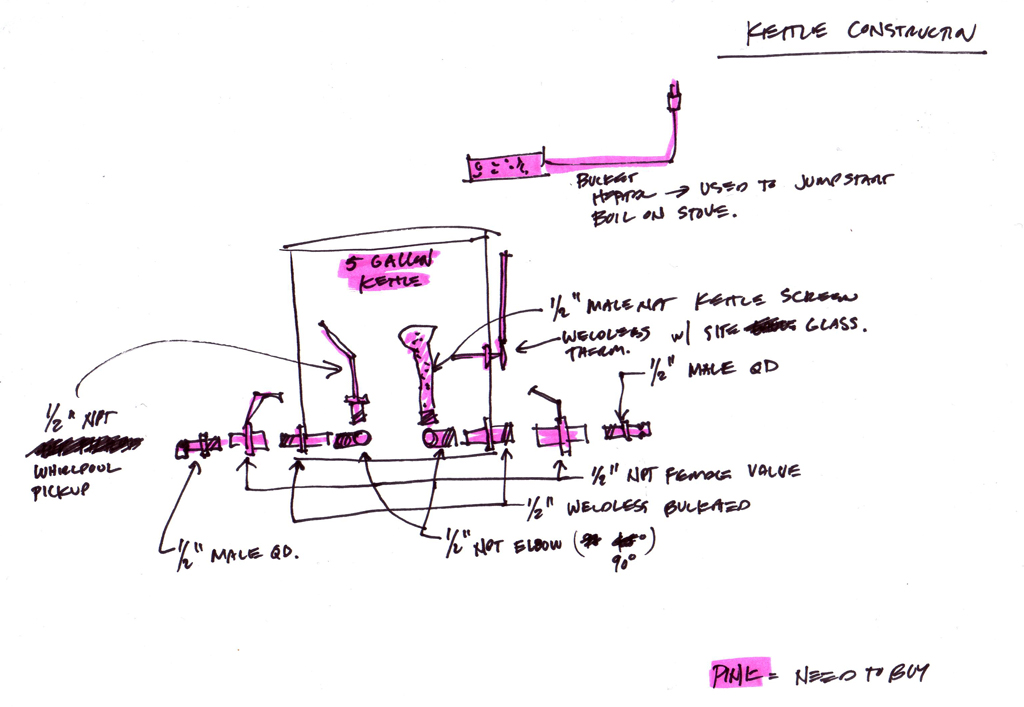

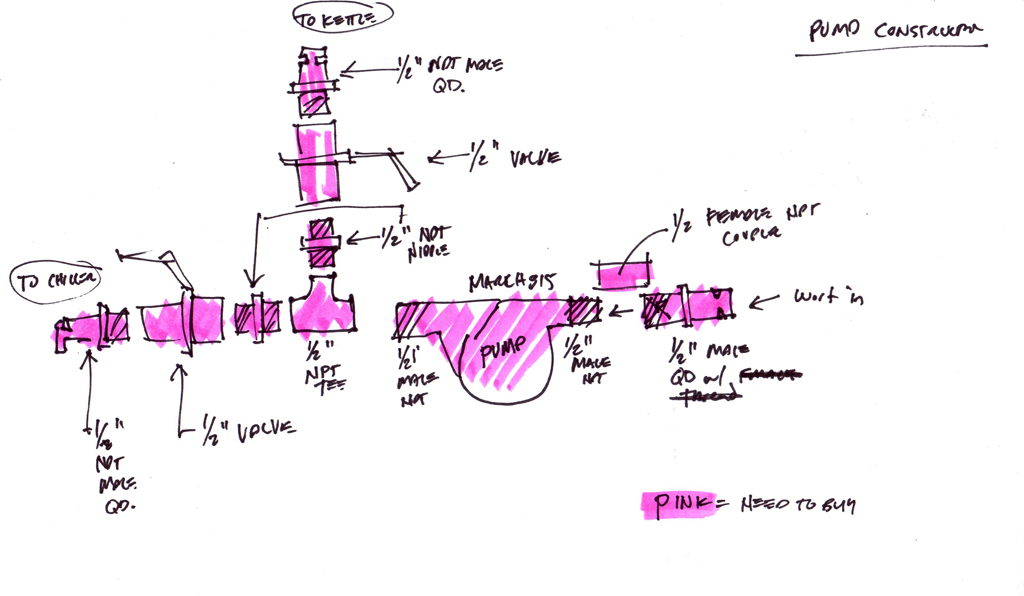

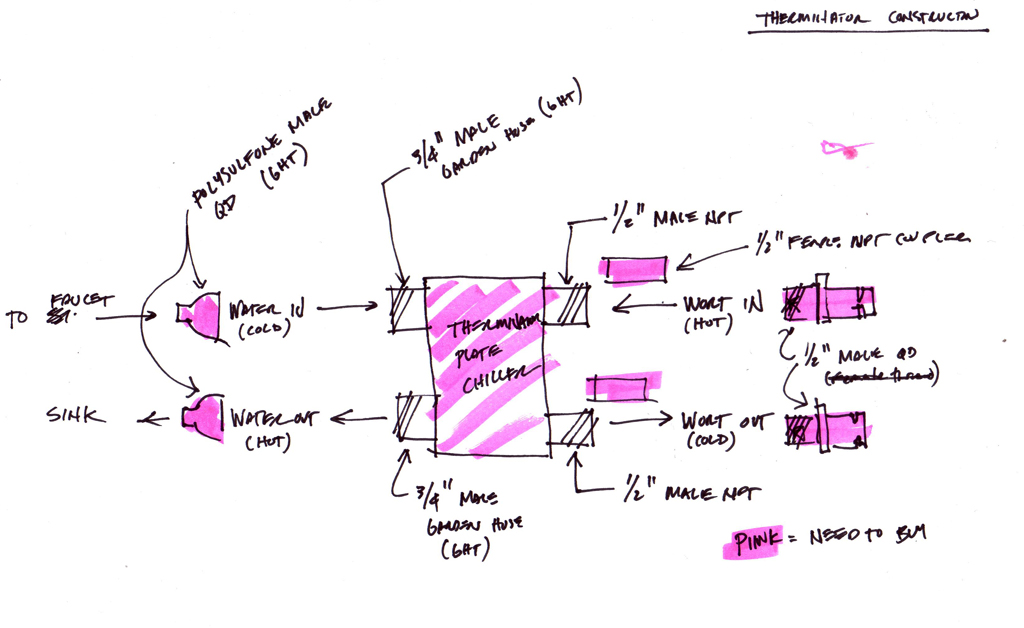

3. Boil, chill, and pitch yeast.

Yeast Pitch:

Final Volume into Fermenter = 2.75 Gallons

Yeast Required = 68 billion (per Mr. Malty)

Yeast Production Date: 6/11/13

Yeast Starter = (None Required)

Fermentation:

1. Chill to 64° F and keep at 64° F until activity slows.

2. Raise temp to 68° F until activity is complete.

3. Crash to 32° F for 36 hours.

4. Keg and force carbonate to 3 volumes CO2.

Brewing Notes:

Gravity Reading – Post boil the wort is quite tart.

– Originally I was shooting for a 1.035 OG using an anticipated efficiency of 68%. My mash efficiency was considerably greater hitting 76%. I adjusted my final volume and interrelated hop additions in order to achieve an original gravity of 1.036.

– After sour mashing for 24 hours I tasted the mash liquid. It was barely tart, but quite clean with no off-flavors. Mash liquid was tasted again after 48 hours and had a substantial clean sourness with no off-flavors.

– My goal was to sour mash for 48 hours, brew, and then have a carbonated keg to serve 7 days later. I did this successfully, serving the carbonated beer less than 7 days from when I pitched my yeast. I rushed my fermentation likely causing the yeast to attenuate to only 1.010. I was hoping for 1.007 (80% apparent attenuation). Had I given the yeast another 2-3 days to work, I believe I would have achieved a 1.007 terminal gravity.