Shipping a sample of your brewing water to an analysis lab, such as Ward Labs, is easy and cost effective.

Water chemistry can be a complicated and intimidating topic. Discussions often quickly turn very technical and jump into the deep end of chemistry. This tends to cause non-scientific brewers to either ignore it completely or apply a blanket approach to water treatment in their brewery.

Part of the difficulty with blanket approaches is that no two locations’ brewing waters are identical. The journey water takes from cloud, to watershed, and ultimately your faucet has an immense impact on the qualities inherent to the water. A personal pet peeve of mine is reading brewing recipes that dictate a blanket approach to water treatment. Instructions–such as adding a fixed amount of gypsum or the ubiquitous ‘Burton Salts’ to your boil or mash–are reckless and naive. These types of instruction must be taken in the context of the specific brewing water that the recipe was formulated with. The results with that specific water may produce a delicious beer, whereas a different brewing water would provide drastically different and often terrible results. These types of blanket approaches automatically raise flags as to the reputable nature of any published recipe.

Blanket approaches should be avoided; a little basic knowledge can go a long way towards improving your beers. The key for homebrewers is distilling the science into practical knowledge that can be applied in the brewery and used to achieve positive impacts on your final beer. With this article, my goal is to establish a pragmatic approach to water treatment, specifically as it relates to brewing with the water flowing through the taps of my Brooklyn apartment.

Water in Brooklyn – Not Just Great for Bagels

The water flowing to my Park Slope / Gowanus apartment originates in the Catskill/Delaware Water System found in Delaware, Greene, Schoharie, Sullivan, and Ulster Counties. The water is surface derived from a relatively pure watershed, so much so that New York City is one of only five large cities in the country with a surface drinking water supply not requiring filtration as a form of treatment. That said, the Department of Environmental Protection does treat our drinking water to prevent any microbial risk. This is typically done with a combination of chlorine and UV light treatment. I have noticed that in warmer months, the chlorine concentration in the tap water seems higher–making it a greater concern for brewers. All of my brewing water goes through a very basic activated charcoal water filter to remove chlorine. I have not seen or heard any evidence that our municipal water is treated with harder to remove chlorimines, which pose the risk of inflicting beer with chlorophenolic off-flavors (band-aid, medicinal).

Purity aside, NYC water is wonderful due to the inherent characteristic of being nearly devoid of the minerals that impact brewing. Our brewing water picks up very little mineral content along its journey from watershed to tap and is about as close to distilled as you can find from a municipal source. This is very beneficial for brewers as it allows you to easily build up your water using various brewing salts and match the ion and mineral concentrations found in nearly any brewing water across the world.

I know a number of brewers in NYC that brew great beer without doing anything to treat their water. This anecdotal evidence supports the fact that very good beer can be brewed with NYC water without any sort of treatment and implies that without having a clear understanding of what you’re adding, it’s probably best to not add anything. That said, there are a number of reasons that I always provide a minimal amount of treatment for my brewing water.

1) Mash pH

The extremely low calcium ion content in NYC water will typically cause the mash pH for lightly colored beers to fall well above the optimal pH range in which amylase enzymes convert starches into fermentable sugar. Almost all beers from straw to brown in color can benefit from some acidification that mineral additions can provide within the mash. For very dark beers (stouts, porter, etc) the mash will typically fall into appropriate mash pH ranges due to the acidic nature of darkly kilned grains. Calcium sulfate (gypsum) and calcium chloride are typically added to my mashes in order to help lower the mash pH into the 5.2-5.4 range.

2) Yeast Health / Flocculation

Various brewing publications cite calcium as an important nutrient for yeast health. Calcium is frequently credited with improving protein coagulation in the kettle and yeast flocculation once fermentation is complete.

3) Flavor

The so-called ‘flavor ions’ sulfate and chloride are a primary concern for brewers. The balance of sulfate to chloride is often cited as a tool for accentuating either hops or malt in a beer. Balancing towards sulfate tends to crisp up a beer and accentuate hops, whereas leaning heavier on chloride tends to round out a beer and accentuate the malt. I typically add calcium sulfate (gypsum) to increase sulfate levels in my water and calcium chloride to increase chloride levels.

Water Analysis

Before attempting to adjust your water, it is imperative to understand what the mineral content of your water is. Luckily, NYC’s Department of Environmental Protection provides an annual report which includes a very useful water analysis:

NYC Dept of Environmental Protection Water Report

Additionally, Ward Labs, can provide brewers with a low-cost water analysis report that includes all of the metrics brewers are interested in.

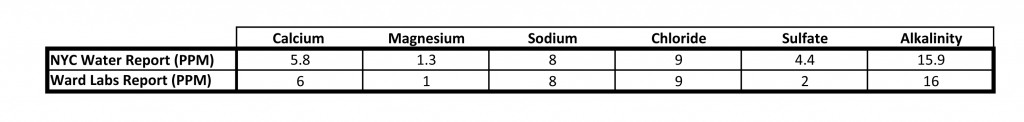

I’ve always been somewhat suspicious of municipal water reports so I went ahead and sent a sample of my tap water to Ward Labs for analysis. As you can see below, the two reports were nearly identical. For reference, I’ve uploaded the test results from Ward Labs here.

The nearly identical numbers from the NYC Water Report and the test analysis completed by Ward Labs.

Calculating Ion Concentration in Your Wort

It is important to understand and quantify the impact that adding a specific quantity of mineral salt has on your water. Luckily, there are many calculators out there that will provide you with ppm concentrations based on your beer ingredients, base water, and mineral additions. I, personally, use and recommend the free EZWaterCalculator spreadsheet. It is easy-to-use and reliably accurate. Additionally, most brewing software provides tools for managing water additions.

Basic Strategies

While not all strategies work for all beers in all locations, below is the basic process I use to brew beer with NYC tap water.

1. Establish a baseline for ion concentrations. For calcium, I typically shoot for 75-100 ppm. For chloride and sulfate, I tend to shoot for 75-100 ppm, balancing towards sulfate if I want to accentuate hops, and chloride if I’m looking to make a malty beer. For very hoppy beers, I’ll push the sulfate levels to 150-200 ppm.

2. In light beers, use a blend of gypsum and calcium chloride to achieve baseline mineral concentrations. The blend will depend on whether I’m looking to accentuate hops or malt. To accentuate hops, I lean more heavily towards sulfate; for malt, chloride. If further pH adjustment is needed to hit desired mash pHs after the mineral concentrations have been achieved, I’ll adjust the mash with lactic acid to hit the desired pH range (5.2-5.4 at room temp). Most light beers that I brew require small additions of lactic acid in addition to mineral salt additions in order to achieve desired pH levels.

3. Most dark beers that I brew tend to land close to the correct pH range without any salt additions. Because of this, I’ll typically create a pH neutral blend of chalk (calcium carbonate), gypsum (calcium sulfate), and calcium chloride to hit 75-100 ppm of calcium and then varying levels of sulfate and chloride depending on whether I’m trying to balance the beer more towards hops or malt. This allows me to hit the ion concentrations I am looking to achieve without pushing the mash outside of the desired pH range.

I’ve been lucky to brew in two locations that have great neutral brewing water (NYC and Seattle). This is certainly not the case in most areas. The overall key for any location is taking a critical look at the water you’re starting with, analyzing the types of beers you want to make, and then making adjustments to your brewing water so that you can achieve optimal brewing results.